Adventures in Time Blocked Planning

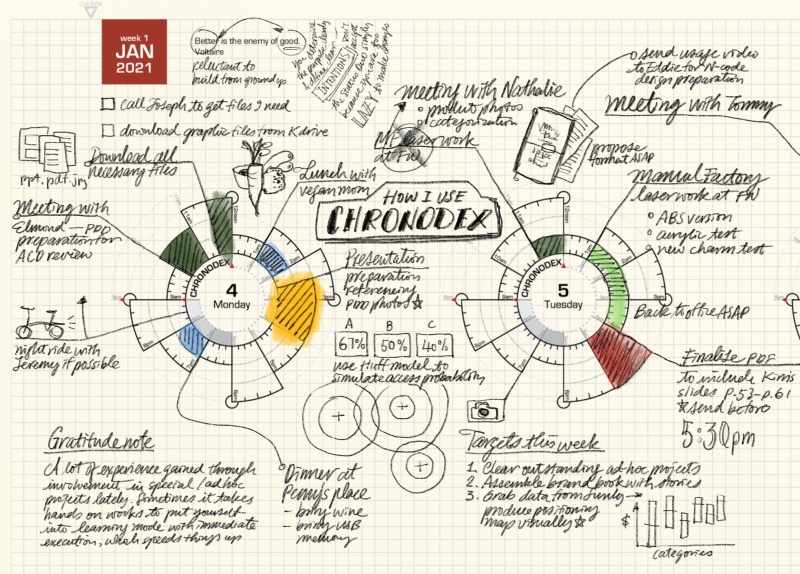

With time blocked planning the idea is to break down your day into blocks of time where you do things. The point is to structure your day so that you’re never faced with the question of “what do I do next?” Instead you sit down ahead of time and block out large sections of time where you do a specific large task, or bundle together a group of small tasks. You don’t block the day out into a minute by minute plan, but instead work in blocks of at least 30 minutes and usually 1-2 hours.

The idea isn’t new, and I haphazardly gave it a try when I was a student, and not surprisingly I failed spectacularly at it. It was only very recently when I decided to give it a serious try. The reason I decided to give time blocking a try was to solve a problem that I think is pretty common: I’d run out of steam about two-thirds into my day and end up just vegging out in the evenings, not accomplishing what I wanted, not even consuming the sort of media that really interested me. There’s only so many decisions my mind could make throughout the day, and late in the afternoon I would run on empty.

Since I was already “front-loading” my day (i.e. doing the really important work first thing in the morning or as early as possible) it was pretty easy to see the benefit of deciding what to do at a given point of time early on in the day, or even the night before. My issue with time blocking in the past had been that my work day is inherently unstructured. I may plan to work on something in the morning, but then a slack message or an email comes in, or someone bursts into the room with a problem and suddenly I’m working on something completely different.

Here, however, is where maturity kicks in. When I gave time blocking a chance years ago, I didn’t really take it seriously as an approach to work and life. Once something interrupted my day (and something always interrupted my day), the plan went out the window never to return. The plans rarely survived until lunchtime, and very quickly I decided that there was little point in time blocking for people like me. What I failed to realize at the time was that the majority of people are people like me: we live in a world where we are constantly being interrupted, and rarely does the day end in the way we envisioned it at the beginning.

Given this new found realization, and the realization that some very smart, very accomplished people whose work I follow use time blocking successfully and consistently, it was clear that the issue wasn’t with time blocking itself but with how I was approaching it. So I decided to make a more consistent, serious attempt to use time blocking for at least a month or two and see where it gets me.

I’m still very early into the process, but I decided to write about it as I go along, so I’ll have a record of how I tweaked things, and for those who like me, wanted to try time blocking but have failed in the past. Maybe my successes and failures will help them in their journey.

The First Mistakes

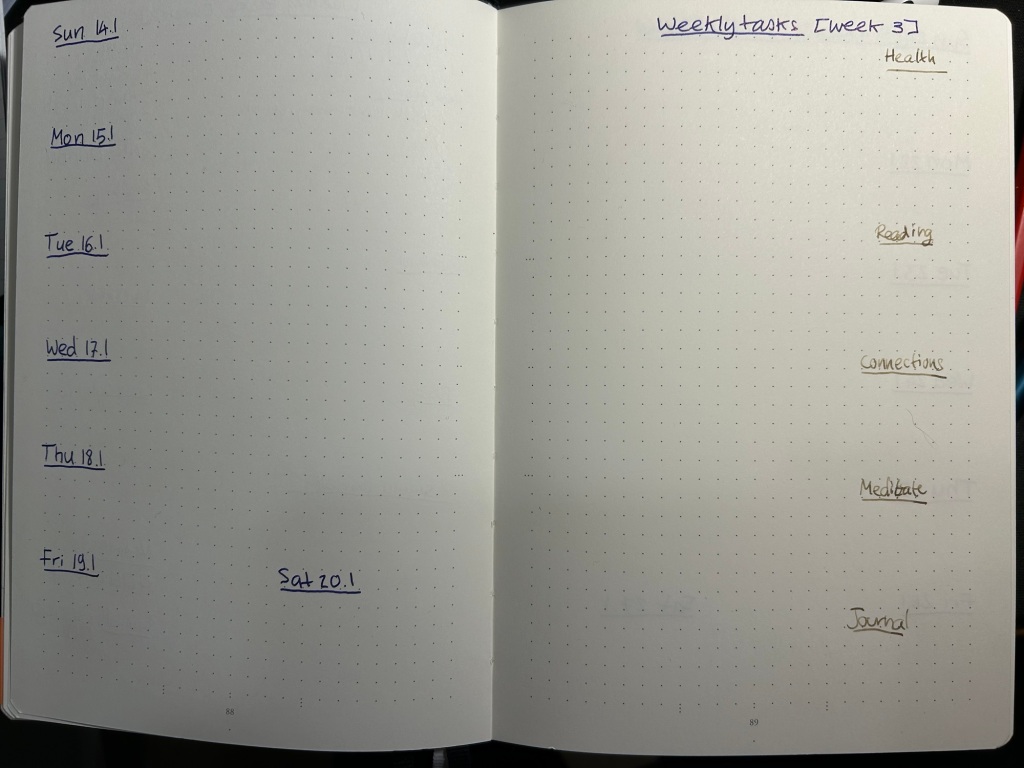

I started out with two mistakes, one easily fixed and another a mistake that I’m still working on correcting. The first mistake was trying to create separate time blocks for my work day and my “home day”. That failed spectacularly. Lesson learned: you need to follow one timeline, one plan, from waking up until going to sleep. If you use two different plans you are setting yourself up to fail because you’re creating two points in the day where you have to switch plans. While the morning switch may be relatively easy, by the time you’re off work you don’t feel like opening a different notebook or calendar and seeing what it is exactly that you’re supposed to be doing right now. I kept my home plan on a Rhodia dot pad and my work plan on a Moleskine squared notebook, and it just didn’t work for me. I had to carry two different plans with me, I had to reference and cross reference them, it was a mess. Now I have one plan per day, on a Rhodia dot pad.

The second mistake is one that I’m still working on correcting, which is what do I do when things don’t go as planned. What I should be doing is taking 5 minutes and replanning the rest of my day basically from that point onwards. What I currently do and doesn’t work well is either try to get back to the plan the moment I can (at which point things start to fall apart pretty quickly), or try to make only minor adjustments to the plan. The reality is that if there’s a significant break in my plan (i.e. something that takes more than 30 minutes to deal with), then I need to take a few minutes to stop and completely reassess my day. No, I will not be able to fit everything I planned into it now. Yes, my energy reserves are most likely more depleted at this point than I originally planned. Rather than trying to stick to the plan and crashing and burning, I need to be kinder to myself and look at what’s left of my day with fresh eyes. “That production outage took a lot from me, so let’s switch things up so I have a lighter workload until I’ve had a chance to recover, maybe even schedule a significant break here. Then rebuild my evening so I also have a bit more recovery time then – add a meditation session, or more reading time, etc.”. This is something I’m currently working on doing consistently.

The First Successes

While I’ve been time blocking only for a short time, I have already seen the value of this system. I’m getting much more done, and I am able to dedicate long stretches of time focused on meaningful work. I batch emails to the beginning and end of the day, and slack messages only to the times between large blocks of deep focus. I haven’t had an episode of mindless YouTube watching in the evenings since I’ve started. I’m reading more, journaling more, meditating more, spending more meaningful time with friends and family. I’m also being much more realistic about my goals. Once you start putting things in the context of the hours you have in the day, it becomes easier to assess how much you can get done in a given day.

It’s not just a result of the time blocking itself, of course. It’s also the way I’ve structured my year, a commitment to deep focus and digital minimalism which mean no social media, no mindless media consumption, more reading and more deliberate practice of the things that matter to me. I’m also far from reaching a point where the way in which I time block my day is stable, well-defined routine. Things are still shifting around as I’m recording in my journal what worked and what didn’t work. While I’m not looking for perfection, I do want to reach a point where I have a system that works for me (and not I for it), and that helps me better shape my days.

I’ll be writing more about time blocking in the future, whether my experiments with it succeed or fail. If you’re giving it a try or use time block planning regularly I’d love to hear your thoughts on it in the comments.